Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Can you imagine going to work for forty hours a week and not getting paid but making a lot of money for your employer? College athletes do it every year across America. Advocates for these athletes have started to question if this is fair or not. States like California have passed a bill that would allow athletes to be compensated by endorsements and sponsorships, which violate the current NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) regulations. This debate has caused a great deal of questions and concerns to be looked at. One major issue is the concern of how to keep it equitable amongst the sexes and different colleges.

According to forbes.com, the NCAA earned $1 billion in 2018. When the discussion on whether or not athletes should be paid, many factors come into play. What would this look like? Opposers to athletes getting paid argue that these athletes are already getting paid through their scholarships. What is not looked at is the extent and amount of these scholarships.

Not every scholarship athlete is getting 100% of their tuition, books, meals, and housing paid for. Some solutions include allowing athletes to collect money based on their ability to get sponsorships and endorsements, but this elite athlete is the minority. What if you are not one of the top athletes in your sport? Then you do not get paid. What if you are not an athlete who plays one of the bigger money making sports like basketball or football? Do you not get paid? The initial thought of paying athletes for their talents outside of their scholarship sounds good until you start thinking of all the issues that come up with allowing that. First being, where will this money all come from and how will it be distributed equally amongst all deserving athletes. It is easy to decide yes athletes should be able to financially benefit from their own talents but with that comes a very large grey area.

As stated by the ncaa.org website, there are 347 Division 1 colleges in America. Only a small number of these colleges actually make money off their athletes, so will the pay be based off what college you go to or will they find a way to make it equitable for all college athletes. Most colleges do not even make enough money yearly to fully support their own athletic department, so again where would this extra money to pay players come from? Not only is there a concern about the equality of pay for athletic abilities and the smaller less popular colleges, but also the issue of fairness to both men and women athletes. This is where discussion of Title IX violations comes into play.

As previously stated in my last blog, it was on June 23, 1972, when a civil rights law named Title IX was put into effect. Title IX states that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” Title IX was developed to ensure equal opportunities for both male and female athletes. If states continue to follow in the footsteps of California and pass bills that say that athletes will be able to get paid for things like sponsorships and endorsements, how will the NCAA keep from violating Title IX regulations? If there are more opportunities given to the most athletic and talented male athletes, could a less popular, talented female athlete have a claim against Title IX regulations? The thought is yes, they could.

Being a Division 1 college “scholarship” athlete, I have a first hand interest in the debate of whether or not to pay college athletes. Before really thinking about this issue, I would have wholeheartedly agreed that athletes should be paid for their time and commitment to their sport. Now I have come to realize there is not an easy solution to be found that would be equal for all athletes. A solution that I feel would be a compromise for all involved would be first to ensure that all Division 1 scholarship worthy athletes have access to a true, full ride scholarship, no matter the sport. If an athlete is talented enough to receive an athletic scholarship and makes the commitment to “work” for a college, then they should not have to pay for any of their college tuition, books, meals or housing. That at least puts all the Division 1 athletes on a level playing field as far as what their scholarship will pay for. As far as the opportunities for extra pay coming from endorsements and sponsorships, I support the NCAA fears that say how would they monitor that or even begin to make it equal amongst women and men athletes. Currently it is difficult enough for the NCAA to “police” violations of athletes accepting any money from outside sources, that if it was now allowed to a certain degree, the NCAA would have its hands full. I believe that if athletes were given the opportunity to financially be rewarded for their talents, it would have negative effects on the culture and integrity of college athletics as we know it today.

Since the beginning of college sports, the athletes competing have been considered to be amateurs, meaning that they are unpaid. On top of this, the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) has set rules that prohibits the athletes to make money off of their name, image, or likeness. Meaning that these athletes can not make money off their talents outside of their scholarship money. In recent times, both of these issues are being questioned as to whether or not they should apply to today. Like I have mentioned in previous posts, back in October of 2019, the NCAA voted unanimously to allow college athletes to be compensated for their names, images, and likenesses. California governor Gavin Newson also signed a bill that would allow college athletes within the state to get paid for endorsement deals and hire sports agents.

The NCAA is responsible for 1,113 schools and over 460,000 athletes. This includes athletes of both genders that are playing for schools both small and large. This brings up the question, “Should there be some kind of equality regarding gender and school size if college athletes were allowed to make money or be paid?”

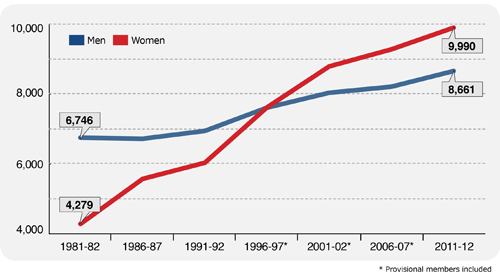

On June 23, 1972, a civil rights law named Title IX was put into effect. Title IX states that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.” Title IX was developed to ensure equal opportunities for both male and female athletes. It is basically saying that the same number of opportunities will be given to both male and female athletes. Before Title IX there was a very big discrepancy in the number of opportunities for male athletes compared to those available to female athletes. This was enacted because at the time female athletes had far less opportunities compared to males. Furthermore, there were limited numbers of scholarships offered to women to play college sports when compared to male athlete scholarships. As a result of this, there were only 30,000 women playing sports compared to 170,000 men. This was created to help even out those imbalances.

An example of how Title IX works can be seen between the baseball and softball programs here at UC Davis. This past fall, the baseball program finished construction of a new covered batting cage. To meet all the requirements of Title IX in building the cages, the baseball team had to make the cages available to the softball team a certain number of hours, to ensure equal opportunity. There have also been numerous cases where universities have been sued for allegedly discriminating against women’s sports and not having the same number of equal opportunities as the men.

The Title IX regulations have put a fear in college athletic programs. Often times I think it has caused the pendulum to swing too far in the opposite direction instead of just providing equal opportunities for both male and female athletes. Why is this issue even brought up when it comes to paying college athletes? The fear is that it could somehow violate the equality of benefits for male and female athletes. If pay was based solely on an athlete’s image and ability, the male athlete might very well be given many more opportunities than a female athlete based on the college sports that bring in the most money and media attention. Would this all fall into a violation of Title IX somehow? In a graph provided by an article in Business Insider, it lists how much each collegiate sport makes in revenue on average. Four out of the top five are male sports and the last four sports listed are female. If college athletes were able to profit off of themselves, obviously the athletes playing the sports that are more popular and bring in the most money would be given more opportunities to profit. Based off of this graph, this would cause the gender factor to heavily favor the male athlete. Would these athletes be restricted on how much they could make due to Title IX violations? Why does this even matter? It all goes back to the current debate surrounding the issue of paying college athletes are not. How will they make a decision that is fair and equitable for males and females, small schools and large schools? The decision, whatever it may be, will affect all college students in some capacity.

Work Cited

Berri, David J. “Paying NCAA Athletes.” Marquette Sports Law Review, vol. 26, no. 2, Spring 2016, p. 479-492. HeinOnline, https://heinonline.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/mqslr26&i=511.

STAUROWSKY, ELLEN J. “College Athletes as Employees and the Politics of Title IX.” Sport and the Neoliberal University: Profit, Politics, and Pedagogy, edited by RYAN KING-WHITE, Rutgers University Press, NEW BRUNSWICK, CAMDEN, NEWARK, NEW JERSEY; LONDON, 2018, pp. 97–128. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2050wq3.8. Accessed 4 Mar. 2020.

“Title IX Enacted.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 16 Nov. 2009, http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/title-ix-enacted.

“Title IX.” Know Your IX, http://www.knowyourix.org/college-resources/title-ix/.

In my last blog post, I discussed about how last October the NCAA (National Collegiate Athletic Association) voted to “start the process of modifying its rule to allow college athletes to profit from their names, images and likeness ‘in a manner consistent with the collegiate model.’” While I was doing research for my last blog post, this seemed like this was the last thing that they have done in regards to this topic. Come to find out, I was wrong.

During my time scrolling through articles, I came across an article, “NCAA, Two Conferences Spend $750,000 on Lobbying,” by the New York Times. This article says, “The NCAA spent $690,000 last year on in-house and outside lobbyists.” According to vocabulary.com, a lobbyist is, “someone hired by a business or a cause to persuade legislators to support that business or cause.” The article goes on to say that some of the larger conferences (Big 12 and ACC) in Division I athletics also spent a large amount of money on lobbyists also. What this is saying is that the NCAA and several conferences have been paying money to people and organizations to get them to support them in what they want. This would make sense due to the fact that this topic has been gaining steam in state governments and is making its way to national legislation. As I have mentioned before, up to 30 states have created bills that would allow college athletes to be able to make money off of their own names, images, and likenesses. A poll by AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found that “about two-thirds of Americans support college players being permitted to earn money for endorsements.”

In what was once an issue where the majority of people agreed with the NCAA has now flipped, leaving the NCAA agreeing with the minority. An article by 247sports, “NCAA, Allies Spent Nearly $1 Million Lobbying Lawmakers in 2019,” believes that this is being done to “influence Congress on ‘legislative and regulatory proposals affecting intercollegiate athletes.’” I believe that the NCAA does not like what these states are doing, and because they feel threatened, this is their attempt to counter.

Subsequently, this is all happening, while the groups that are in favor of athletes being paid, are not bribing any lobbyist with money. While this might seem like something that could inevitably change the outcome to be in the NCAA’s favor, Tom McMillen, President and CEO of the LEAD1 Association, a trade group for Division I athletic directors, believes the opposite. In the same New York Times article, McMillen says that, “You can have all the lobbyists in the world, but it doesn’t really make a difference,” while Rep. Mark Walker (R-N.C.) believes there’s “no question” the NCAA has been effective in lobbying for its own goals. He believes this because there has been “little to nothing done” and that if the athletes had the correct federal representation “we’d be much further down this path than we are.”Therefore, I agree more with Walker’s statement. As I have said before, not much has really happened recently and I feel like this could be some of the reason why. An article by whio.com says that, “Organizations like the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) want Congress to come up with national rules for how and when college athletes get paid.”

It is critical for something to be decided soon, before each state has its own laws regarding athletes getting compensated. An athlete deciding which school to attend, will go to the state which offers the most compensation, which changes the playing field. I don’t understand why everything becomes an issue surrounding money. We can no longer trust the process because we have people able and willing to “pay” lobbyists to vote and fight for their interests. So it would only make sense to pay the people who make these decisions so that when and if it happens, the decision will be in their favor.

After completing my previous post, I do not believe that athletes being paid by the universities would be a successful way to handle this issue. As previously posted, many colleges rely on student fees to fund their athletic programs and even then, most of them aren’t making enough profit to fully fund their own programs. How would this even be possible knowing that most college athletic programs are funded by student fees found in tuitions? I do not think it is fair to potentially raise fees for all students, just so athletes can get paid. Additionally, many of these athletes are paying those same fees when they pay their tuition costs.

Upon further research, I found that there is another way that college athletes could be paid. According to Dan Murphy of ESPN, back in October of 2019, the NCAA voted to “start the process of modifying its rule to allow college athletes to profit from their names, images and likeness ‘in a manner consistent with the collegiate model.’” This happened because of California passing its “Fair Pay to Play Act,’’ which I have mentioned in previous posts, that the NCAA called it an “existential threat” and vowed punishment. This is saying that the NCAA, the organization that regulates student-athletes, is willing to work to find a way to allow the athletes to make money off of themselves without the universities being responsible for that. In my opinion, this would be the most reasonable way to begin solving this issue. Instead of putting it on the universities, it is the athletes job to find ways to make money. An editorial from, The Columbus Dispatch, says that this way “wouldn’t cost schools a dime and that it would simply allow athletes to hire agents and endorse products. This comes at a time when money has turned college sports into a professional operation, but the people it depends on the most are treated like amateurs.”

I believe that this solution would be the best of both worlds. The universities would not have to take a financial hit in paying their athletes and the athletes would be able to use their name, image and likeness to their advantage as a way to make money. I don’t really know why this would be an issue. Athletes have a very good argument when they question how a school can make so much money off of them, but the athlete themselves is forbidden to profit. If someone is given the opportunity to endorse themselves or their talent, then they should be able to do it.

This whole conversation started after O’Bannon v. NCAA. This case began after Ed O’Bannon, a former UCLA basketball player, noticed that a video game included a player that matched the same profile as him even though he never authorized this. According to fanbuzz.com, O’Bannon v. NCAA “argued that student-athletes were entitled to financial compensation post-graduation.” This case “grew into a movement to help the student-athletes working, essentially, pro bono for billion-dollar institutions.”Of course there are still some questions to be answered, ones that deal with issues regarding equality amongst gender and different sports, which become more issues for the NCAA to figure out. A main concern is that the NCAA has done nothing to address this issue. They are sitting back waiting and watching as states make their own rules and how the government plans to intercede. Other states, twenty-three to be exact, are in the process of working on proposals like that of California’s in an attempt to pressure the NCAA to kickstart their response to them. Each state having its own regulations will not be the answer. The issue needs to be resolved by a national policy that is consistent no matter what state the athlete is in. This would mean that the court system, the federal government and the NCAA all agree upon some resolution regarding the paying of athletes. I hope that the integrity of college sports is the top priority and truly full-scholarships are considered for all deserving athletes, and it does not become a big business model.

When looking at the different sides of the college-athlete getting paid or not , I have never considered the point of view of the non-athletic student. One of the driving thoughts of this topic is that coaches and athletic directors make money off of the play of these athletes but athletes do not see a penny of it. Some believe that since it is the athletes “performing” they should receive something for it while others believe that scholarships are the compensation supplied to the athletes from the university. What about the students who are attending colleges and not playing any sports, but are expected to pay for the athletic programs at their school through part of their tuition fees? In the article, “Students Paid the Majority of UC Davis’ 2018-2019 Athletic Budget,” writer Graschelle Farinas Hipolito discusses a very sensitive topic, which I find interesting when thinking about the “Pay to Play” debate. When looking for articles about college athletes getting paid, my eyes immediately stopped at this article written by Hipolito. How could it not? I am a student athlete for the UC Davis baseball team, who is here on an athletic “scholarship.” No wonder academic students have such an issue with the whole athletic thing, just from the title of this article! Of course, my curiosity got the best of me and I had to read this article.

Hipolito begins by stating “students at UC Davis directly fund athletics. For 2018-2019, the NCAA reported that student fees made up $23.5 million, or about 57%, of UC Davis’ athletics budget.” Intercollegiate Athletics (ICA) at UC Davis receives student funding through student fees. When I looked on the UC Davis webpage there was a section that showed the tuition and fees “breakdown.” There are many lists of fees that a student is expected to pay and one of them is Student Services Maintenance Fee/Student Activities and Services Initiative Fee that includes 25 Division 1 Varsity Sports teams, 39 Club sports and 29 Intramural programs. This is not something that just UC Davis does. Many other Big West schools operate with similar percentages of money from student fees going towards funding athletics, so UC Davis is not doing something that is not happening in other colleges. These fees increased when UC Davis decided to move to Division I athletics. Prior to this they were competing in the NCAA Division II and supporters of moving to Division I athletics pushed forward to see this change happen. Well it did. Following the approval of the 2003 Campus Expansion Initiative, the 2004-2005 UC Davis sports teams competed in Division I schedules. This change could only be possible with the increase in student fees to help fund UC Davis athletics.

Furthermore, UC Davis does not have athletic programs that can generate enough revenue to support their teams, as do many others. According to Justin Wann of Lincoln Journal Star, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, one of fewer than two dozen to turn a profit while charging no student subsidy for sports, which also receives millions annually from its athletic department. Because so few athletic departments operate in the black, directly paying athletes – the model used in professional sports – is impossible at the college level. This shows that UC Davis isn’t the only school that relies on student fees to help fund athletics. There are 347 Division I athletic programs in the United States and there are only fewer than 24 that don’t need student support to make a profit. I am leaning more towards what the author is saying about it being impossible for the universities to directly pay their athletes. The only way a school like UC Davis can have Division I athletic programs is through student fees and outside donations.

I think that, for most schools, money received from student fees would better serve as ways to upgrade existing facilities or to fund sports programs that might be underfunded. If people became really serious about allowing athletes to be paid, there would need to be a different solution.

I have been around sports and been part of athletic teams my entire life. I can see how students who come to UC Davis, who are not in support of athletics, have a hard time with these added costs to an already high tuition cost. UC Davis has always been and always will be a high academic college. Having Division I athletes come to UC Davis, in my opinion, will only enhance the college experience for everyone who attends. Sports go beyond just shooting a ball into a hoop. Being part of athletics has brought a lot to my life and has been a large part of who I am. Just being a good athlete was not my “free” ticket into UC Davis. I had to be accepted through admissions just like any other student. I had to prove through my academic success, that I was worthy academically to attend UC Davis and playing baseball was just an added bonus. Again, it is not free for me to attend. I have to pay quite a bit of money to attend here, even with a partial scholarship. I am paying those same fees literally out of my pocket that make Division I athletics possible at Davis.

In conclusion, this fact that UC Davis students financially support the athletics at Davis is not something just Davis students pay. It is very common with the many extra fees the tuition has embedded in it at many colleges. This article brought to light for me how the opposers of student-athletes getting paid to play have some valid arguments as to why they feel it is not ok. Unlike I previously thought, there are only a few athletic programs in the country that make enough money to possibly be able to afford to pay their athletes. So how would this work for universities like Davis that rely on students fees to run their athletic programs? Where would this money come from? This issue is not easily solved but through the many discussions it is causing, there has to be some equal ground that everyone can stand on.

College athletes have never been paid or been allowed to make money off of themselves for playing sports at their schools. In the months leading up to the start of this school year, I had to fill out many forms from the school and the NCAA proving that I have never taken money from a booster, been given special monetary accommodations from any youth teams, or used my name or image as a way to make money. All of these forms are used to show that I had followed the NCAA rules and should be granted eligibility to play college athletics. This is all because of what I mentioned before. To be able to play you cannot have broken any of these rules. For example, I could not get paid from a business to endorse their product or whatever it is that they do. But in recent years, people have brought up the idea that college athletes should be able to make money from the school or from endorsements that use the athletes name, image, or likeness. Being a student-athlete here at UC Davis I find this topic interesting and care about it because I have gotten to witness first hand what it takes to be a student-athlete while also dealing with the rigorous demands of being a student also. I also find it interesting that some people believe that we should get paid for doing what we do on top of other things we receive.

Dan Walker, a writer for the USA Today, writes about the upcoming NCAA Convention that will be taking place in California. Walker states the irony behind this years’ convention being held in the state that has recently passed a bill “Fair Pay to Play Act.” This bill makes it “illegal for schools in the state to prevent college athletes from being compensated for the use of their name, image and likeness by 2023.” This bill would also allow NCAA athletes to be able to profit off of their names, images, and likeness. With the current NCAA rules, doing any of these things would result in a possible loss of eligibility. I feel one of the problems that arises is when you are only talking about a small percentage of college athletes that actually bring in the millions of dollars that are discussed with this issue. What about the “average” college athlete that goes to a school that doesn’t have the money making programs with big basketball or football programs?

Consequently, several other states are attempting to follow Califonias’s example. According to azcentral.com, “17 states including Arizona have filed or pre-filed NIL bills with 15 more planning to do so.” I was very surprised to see that there could possibly be 32 states to allow this. I think that it will be interesting to see if all of them actually follow through and follow California’s lead.

College athletic administrators meet at the NCAA convention to vote on and discuss policy changes needed for collegiate athletics. This year’s discussion will most likely revolve around student-athletes being able to be paid outside of their scholarship. The NCAA president Mark Emmert, told USA Today, “it’s difficult to give schools guidance about what to do or where this is all going given the differences in the various state legislative bills that have been proposed and the potential for federal legislation, which may or may not happen given both the historical slowness of Congress and the political inertia of the election year.” Emmert said bills going into effect during 2020 would be “very, very disruptive to college sports.” I agree with this statement about it being disruptive. I believe that it would be wise for both parties to take their time and make sure that they think this through without jumping to something that destroys college athletics. College sports are very popular in our country and it would not be productive to rush something like this that could possibly have a negative impact on the sport. However, I do agree that some changes need to take place in order to help scholarship-athletes like myself, who do not receive “full” scholarships, get their education fully funded because it feels as if I have two full-time jobs; one a full time student and second, a full time athlete. It is literally impossible for me to have another job that actually pays me an actual salary.

Walker goes on to state that the NCAA has been dragging its feet when it comes to this issue. Questions NCAA must consider, according to Walker, include; what kind of regulations would be in place regarding athletes accepting endorsements, how can everyone profit equally, and how would any payments be distributed. President Emmert appears to be concerned that moving towards paying athletes moves away from the collegiate model which has given student-athletes a great opportunity up to this point. He also agrees there is a need to “modernize and make some changes” but stresses this must be done with caution and well thought out thinking. This statement agrees with what I had to say earlier. I think that it would be wise to take a more cautious approach to this subject. There are questions and concerns that need to be answered and if this idea were to really take shape it would need to do so in a way that still keeps the spirit of what college sports are about. These athletes aren’t professionals and in some people’s minds, should not be treated like they are. I don’t believe college athletes should be handed thousands of dollars in compensation but consideration needs to be taken for the fact that athletes are not able to have money making jobs due to the time commitment of playing a sport, and scholarships do not cover all college costs for athletes. My hope is that this discussion will see both sides of the issue and come up with a compromise that benefits all involved, while keeping the integrity of college athletics.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.